Read Time

5 min

The following is a guest post written by Ashwin Wadekar, former Chief of Staff at Gorillas.

→ Read HNGRY founder Matt Newberg's response to this op-ed here.

If 2021 was the craze of quick commerce, 2022 was the hangover. To cap off a turbulent year for the industry, the biggest news of all dropped. Getir was set to acquire Gorillas– a fittingly loud ending for the tumultuous Berlin-based startup.

A reported $1.2B sale, even if all-stock, is no small achievement for a startup. Still, Gorillas sold for less than the capital it raised, and at times much more seemed possible for the fastest company to achieve unicorn status in Europe.

The reaction was predictable and immediate: lacking real defensibility, quick commerce grew out of fortuitions timing and venture-backed discounts. Rather than improving infrastructure, leadership aggressively expanded before it was ready. The company struggled to maintain its cash burn and was forced to shut down markets and lay off hundreds of employees. It was hardly alone: JOKR, Gopuff, and Flink all faced similar retreats.

Out of an apparent equilibrium, a structural flaw emerges

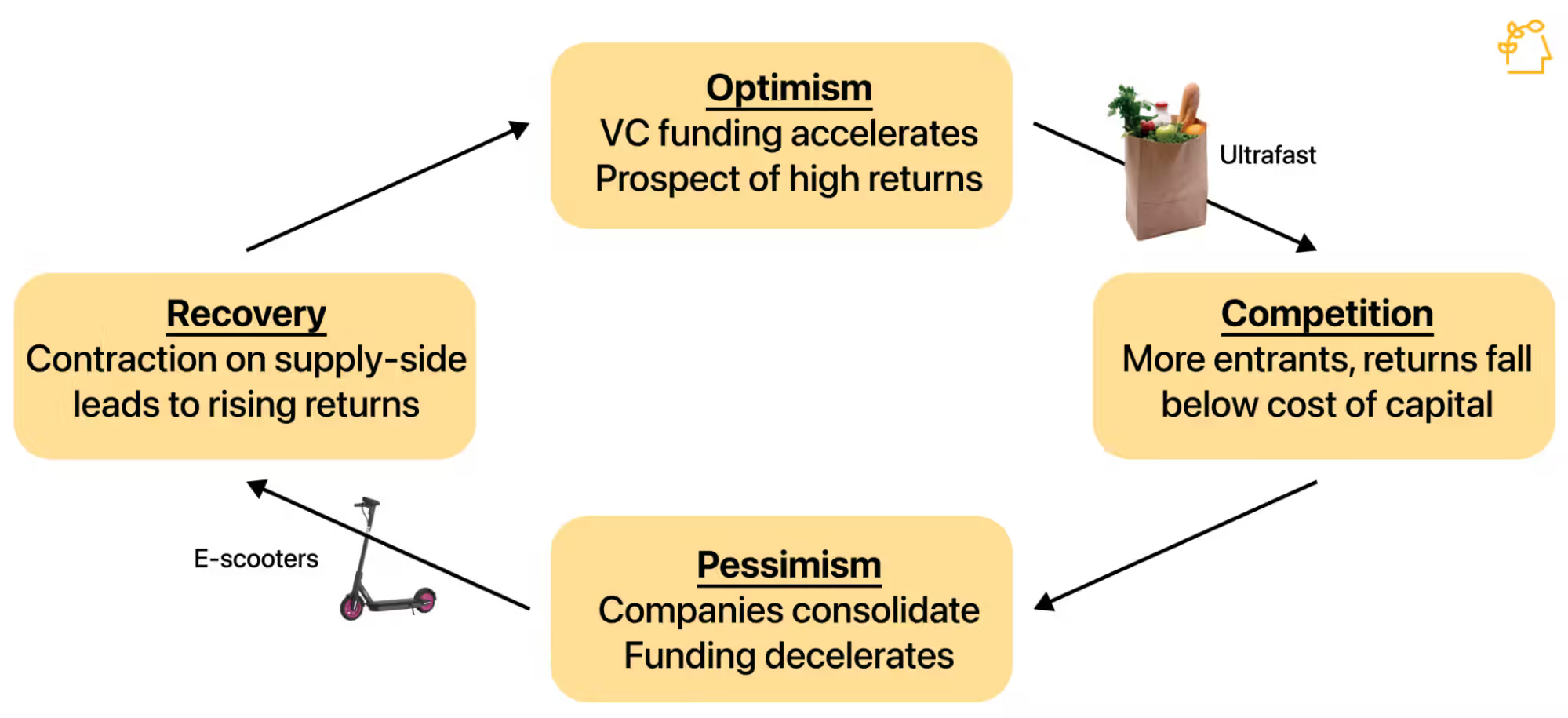

Rather than assessing these defeats solely as industry management failures, it could be instructive to view them as the consequence of a system clogged with too much capital. Quick commerce companies made big, bold bets because they needed to beat well-capitalized competitors to market. Because venture capital returns derive from a few big winners– and because quick commerce represented a fashionable, high-margin solution in an enormous market– VC firms had every incentive to invest. In short, both sides of the ecosystem responded rationally to the incentives in front of them.

An overabundance of capital allowed too many companies to receive funding, leading to deal cycles that were too short for them to mature. Sustainable markets couldn’t develop and customer habits didn’t stick. In 2021, eight quick commerce companies operated in New York City; now, only three remain. In Europe, ten quick commerce companies vied for billions of dollars of funds. Most have closed operations.

It wasn’t always this way

Had quick commerce existed in a different era, it might have looked more like ridesharing in the 2010s. Outside of Uber and Lyft, only a handful of upstarts, such as Gett and Juno, received meaningful funds. As a result, more of the capital in the space was devoted to building a sustainable customer habit, with considerably less pressure from ever-quickening deal cycles. And while famously competitive, Uber and Lyft still had time to mature operationally and technically on their quest for free cash flow– a journey that continues to today, nearly 14 years after the companies launched.

Instead, quick commerce companies have had only a fraction of that time. Gorillas simultaneously launched throughout Europe and the US in its first year, whereas Uber didn’t expand internationally for three years. Why the rush for Gorillas? A slew of upstarts, inspired by the industry’s rapid growth, seemed poised to seize greenfield markets and dissuade new entrants, which could have stifled revenue growth at a time when it was most prized. The strategy of aggressive expansion received ample backing from investors, and in many ways seemed to pay off: Gorillas achieved unicorn status in just ten months, while Uber took four years to hit that same mark.

As though a movie on fast-forward, the industry rushed through its natural lifecycle on a quest to serve customers in every major global market. But changing customer behavior works on a more gradual timeline: Uber and Lyft took years assuring passengers it was safe to ride in the backseat of a complete stranger, and DoorDash (and other restaurant delivery platforms) spent the better part of a decade convincing customers to stay home and order in. Meanwhile, quick commerce had to build a market in just a year or two.

The discrepancy in these timeframes show just how rapidly quick commerce companies were asked to develop, even though operating physical warehouses typically take at least a year to show returns. The conflict between ambition and reality grew too much for the industry to bear. Efforts at profitability– retail partnerships, private label, prepared foods, and even consolidation– launched swiftly and to great effect, but they ultimately fell short in closing the profitability gap. The unit economics of first-party delivery are challenging enough, but the structure of the game made them even harder.

A Gorillas warehouse located in the ground floor retail of an apartment complex in Brooklyn, New York (Source: Kitchn)

A parallel game plays out

But here’s the problem: venture capital firms themselves had to play the same game as the companies they funded. In the US, the same number of venture capital firms raised over 50% more money in 2021 than the year before. Attracted to a strong track record of returns, LPs overwhelmingly supported these fundraises, allowing undeployed capital to reach an all-time high at $223B. And VCs went to work, funding 27% more deals than the year before at an ever-quickening pace.

Flush with historic amounts of capital, venture capital firms drove up valuations, lowering prospective returns in an effort to join the capitalization table of hot commodities like Gorillas. But underneath the social pressure lay an economic one: a couple of big quick commerce winners could deliver returns for an entire portfolio. And online grocery had reached record growth rates; would there ever be a better time to fund the capital-intensive model? It seemed irrational not to invest.

The incentives of the startups and investors began to mirror each other. Just as Gorillas and Getir, empowered by endless capital, sought to maximize growth before the next fundraise, well-funded VCs were forced to outbid each other to access the prospective returns of a white-hot industry. Both management and investors acted reasonably: companies seized the chance to solve a customer problem, and investors were intrigued by the margin opportunity of vertical integration in an ecosystem where marketplaces like DoorDash generate only 3% contribution margins per order.

Maybe next time

What could have been an orchestrated effort to transition customers to a new method of consumption turned into an arms race. So when the capital markets shifted and investors eyed profitability, only incumbents like Getir and GoPuff, equipped with several years of operational prowess in core markets, were able to deliver. There’s the irony: with less capital in the system, more players might have survived and more customers could have been served. And that’s the real shame, because for all its infamy, quick commerce has real potential as a sustainable model.

Capital availability typically enables innovation. But if quick commerce is any indication, too much money can also prevent new services from taking hold. We’ve reached a more even fundraising environment now; that’s probably positive for entrepreneurship at large. But bull markets will return, and once again we will be forced to grapple with the consequences of massive amounts of highly concentrated wealth.

Maybe next time, we’ll be ready.